|

To many of us, John Wayne has entertained

us for decades, on both the big screen and on our television

sets. Throughout most of his career, John Wayne played the part

of the man who stood for what was right against the evil in this

world. Even when he played the part of the man who was in the

wrong, such as in Red

River, he was still an on-screen hero.

Sure, Wayne was just an actor. He wasn’t even

John Wayne. He was born Marion Michael Morrison in

Winterset, Iowa May 26, 1907. However, John Wayne represented

America and the Old West, maybe not exactly the way that it

really was, but the way that we would like for it to have been.

He has effected the hearts and minds of the people of this

country more than most Presidents have or ever will. He has

inspired patriotism when it was sorely lacking in our country.

Before we go into the life of John Wayne too deeply, let’s

look at the gun that Ruger has created as a tribute to

the one hundredth anniversary of his birth.

I have reviewed the Ruger New Vaquero

twice before; once when it

first went into production, and again

about a year later. This New Vaquero featured here

differs very little from those earlier New Vaqueros, except in

the detail of its fit and finish. I have found every New Vaquero

that I have fired to shoot very well. In the New Vaquero, Ruger

corrected some of the long-standing criticisms of the New Model

Blackhawk and Vaquero designs. The chamber throats on .45

caliber New Vaqueros are of the proper size, with those on this

John Wayne gun measuring a perfect .4515 inch diameter. That is

just the right size for shooting cast .452 diameter bullets, and

also works well for .451 jacketed bullets.

On this John Wayne sixgun, Ruger wisely chose to

give the gun a nice polished blue finish, instead of the

case-colored frame of the standard New Vaquero. The grips are

checkered walnut, and have the initials "JW" inscribed

into them on each grip panel near the bottom. The frame, barrel,

grip frame, and cylinder are engraved in a light scroll pattern

that is nicely done, and tasteful. The engraving looks

much better than most of the engraving that I have seen on other

Ruger revolvers recently. It is of course machine engraved, but

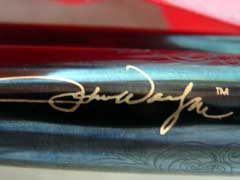

it looks darn good. John Wayne’s signature is inscribed

in gold atop the barrel. This John Wayne revolver seems to be

fitted better than the average New Vaquero also. I have examined

five of these personally, and all are as well done as is mine.

These John Wayne sixguns have a special serial number range,

which is highly unusual for Ruger to do. The serials start at

JW001 and run through JW03500. Mine is JW00071. Like all New

Vaquero revolvers, the chambers line up correctly with the

loading gate for loading and unloading. It also has the new key

lock, which is hidden beneath the grips. One must drill a hole

in the right grip panel to use the key lock feature. Mine will

never be drilled, as the feature is not needed, but is

unobtrusive and there if the owner desires. The barrel/cylinder

gap on my sample measures a nice even .003 inch. The trigger

pull measured about four and one-quarter pounds as delivered,

but a quick Poor Boy’s Trigger Job

improved that dramatically. These guns come from the

factory with a plastic wire tie around the hammer to preserve

the perfection of the cylinder finish, if the owner chooses to

not fire the sixgun.

Shooting the John Wayne Vaquero proved to be a

real pleasure. Firing offhand at 25 yards, the sights were dead

on for me. I really like that. All three of my New Vaquero

revolvers are sighted correctly for my chosen loads, and that

makes things real handy. I now have .45 Colt New Vaqueros in all

three barrel lengths; four and five-eighths (this John Wayne

gun), five and one-half, and seven and one-half inches.

Shooting the John Wayne Ruger from the Ransom

rest at 25 yards, the gun performed very well, grouping

five shots within one and one-half inches, and ten shots right

at two inches, with two different handloads. I fired no jacketed

bullets through this Ruger. It will have a life of shooting my

favorite .45 Colt bullet; the Mt.

Baldy 270 SAA, pushed to about 800 feet-per-second. That

bullet weighs in at about 285 grains lubed.

The John Wayne Ruger comes packaged in a

specially-marked red plastic hard case, with a special outer

sleeve and booklet.

I am very glad to see that Ruger is offering

this tribute to John Wayne. The man was a true American, on and

off the screen. I did not know him, except through his movies.

However, I am honored to own and shoot this gun which is a

tribute to John Wayne, who himself was a tribute to the way that

America should be.

Check out the full line of Ruger products

here.

For the location of a Ruger dealer near you,

click on the DEALER FINDER icon at www.lipseys.com.

Jeff Quinn

|

To locate a dealer where you can

buy this gun, Click on the DEALER FINDER icon at: |

|

|

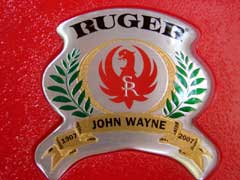

John Wayne 1907-2007

For a brief biography on John Wayne, I am

not qualified to do such, but instead I will refer you to this

biography written by his close friend, and our former president,

Ronald Reagan. It was written shortly after Mr. Wayne’s

death in 1979, and was published in the Reader’s Digest:

Unforgettable John Wayne

biography by Ronald Reagan

courtesy of Readers Digest - October 1979

We called him DUKE, and he was every bit the

giant off screen he was on. Everything about him - his stature,

his style, his convictions-conveyed enduring strength, and no

one who observed his struggle in those final days could doubt

that strength was real. Yet there was more. To my wife, Nancy,

"Duke Wayne was the most gentle, tender person I ever

knew."

In 1960, as president of the Screen Actors'

Guild, I was deeply embroiled in a bitter labor dispute

between the Guild and the motion picture industry. When we

called a strike, the film industry unleashed a series of

stinging personal attacks on me - criticism my wife found

difficult to take.

At 7:30 one morning the phone rang and Nancy

heard Duke's booming voice: "I've been readin' what these

damn columnists are saying about Ron. He can take care of

himself, but I've been worrying about how all this is affecting

you." Virtually every morning until the strike was settled

several weeks later, he phoned her. When a mass meeting was

called to discuss settlement terms, he left a dinner party so

that he could escort Nancy and sit at her side. It was, she

said, like being next to a force bigger than life.

Countless others were also touched by his

strength. Although it would take the critics 40 years to

recognize what John Wayne was, the movie going public knew all

along. In this country and around the world, Duke was the most

popular box-office star of all time. For an incredible 25 years

he was rated at or around the top in box-office appeal. His

films grossed $700 million - a record no performer in Hollywood

has come close to matching. Yet John Wayne was more than an

actor; he was a force around which films were made. As Elizabeth

Taylor Warner stated last May when testifying in favor

of the special gold medal Congress struck for him: "He gave

the whole world the image of what an American should be."

Stagecoach to Stardom

He was born Marion Michael Morrison in

Winterset, Iowa. When Marion was six, the family moved to

California. There he picked up the nickname Duke - after his

Airedale. He rose at 4 a.m. to deliver newspapers, and after

school and football practice he made deliveries for local

stores. He was an A student, president of the Latin Society,

head of his senior class and an all-state guard on a

championship football team.

Duke had hoped to attend the U.S. Naval Academy

and was named as an alternate selection to Annapolis, but the

first choice took the appointment. Instead, he accepted a full

scholarship to play football at the University of Southern

California. There coach Howard Jones, who often found

summer jobs in the movie industry for his players, got Duke work

in the summer of 1926 as an assistant prop man on the set of a

movie directed by John

Ford.

One day, Ford, a notorious taskmaster with a

rough-and-ready sense of humor, spotted the tall USC guard on

his set and asked Duke to bend over and demonstrate his ball

stance. With a deft kick, knocked Duke's arms from his body and

the young athlete on his face.

Picking himself up, Duke said in that voice

which then commanded attention, "Let's try that once

again." This time Duke sent Ford flying. Ford erupted in

laughter, and the two began a personal and professional

friendship which would last a lifetime.

From his job in props, Duke worked his way into

roles on the screen. During the Depression he played in grade-B

westerns until John Ford finally convinced United Artists to

give him the role of the Ringo Kid in his classic film Stagecoach.

John Wayne was on the road to stardom. He quickly established

his versatility in a variety of major roles: a young seaman in Eugene

O'Neill's The

Long Voyage Home, a tragic captain in Reap

the Wild Wind, a rodeo rider in the comedy - A

Lady Takes a Chance.

When war broke out, John Wayne tried to enlist

but was rejected because of an old football injury to his

shoulder, his age (34), and his status as a married father of

four. He flew to Washington to plead that he be allowed to join

the Navy but was turned down. So he poured himself into the war

effort by making inspirational war films - among them The

Fighting Seabees, Back

to Bataan and They

Were Expendable. To those back home and others around

the world he became a symbol of the determined American fighting

man.

Duke could not be kept from the front lines. In

1944 he spent three months touring forward positions in the

Pacific theater. Appropriately, it was a wartime film, Sands

of Iwo Jima which turned him into a superstar. Years

after the war, when Emperor Hirohito of Japan visited the

United States, he sought out John Wayne, paying tribute to the

one who represented our nation's success in combat. As one of

the true innovators of the film industry, Duke tossed aside the

model of the white-suited cowboy/good guy, creating instead a

tougher, deeper-dimensioned western hero. He discovered Monument

Valley, the film setting in the Arizona - Utah desert where a

host of movie classics were filmed. He perfected the

choreographic techniques and stuntman tricks which brought

realism to screen fighting. At the same time he decried

pornography, and blood, and gore in films. "That's not sex

and violence," he would say. "It's filth and bad

taste."

"I Sure As Hell Did!"

In the 1940s, Duke was one of the few stars with

the courage to expose the determined bid by a band of communists

to take control of the film industry. Through a series of

violent strikes and systematic blacklisting, these people were

at times dangerously close to reaching their goal. With

theatrical employee's union leader Brewer, playwright Morrie

and others, he formed the Motion Picture Alliance for the

Preservation of American Ideals to challenge this insidious

campaign. Subsequent Congressional investigations in I947

clearly proved both the communist plot and the importance of

what Duke and his friends did.

In that period, during my first term as

president of the Actors' Guild, I was confronted with an attempt

by many of these same leftists to assume leadership of the

union. At a mass meeting I watched rather helplessly as they

filibustered, waiting for our majority to leave so they could

gain control. Somewhere in the crowd I heard a call for

adjournment, and I seized on this as a means to end the

attempted takeover. But the other side demanded I identify the

one who moved for adjournment.

I looked over the audience, realizing that there

were few willing to be publicly identified as opponents of the

far left. Then I saw Duke and said, "Why I believe John

Wayne made the motion." I heard his strong voice reply,

"I sure as hell did!" The meeting and the radicals'

campaign was over.

Later, when such personalities as actor Larry

Parks came forward to admit their Communist Party

backgrounds, there were those who wanted to see them punished.

Not Duke. "It takes courage to admit you're wrong," he

said, and he publicly battled attempts to ostracize those who

had come clean.

Duke also had the last word over those who

warned that his battle against communism in Hollywood would ruin

his career. Many times he would proudly boast, "I was 32nd

in the box-office polls when I accepted the presidency of the

Alliance. When I left office eight years later, somehow the

folks who buy tickets had made me number one."

Duke went to Vietnam in the early days of the

war. He scorned VIP treatment, insisting that he visit the

troops in the field. Once he even had his helicopter land in the

midst of a battle. When he returned, he vowed to make a film

about the heroism of Special Forces soldiers.

The public jammed theaters to see the resulting

film, The

Green Berets. The critics, however, delivered some of

the harshest reviews ever given a motion picture. The New Yorker

bitterly condemned the man who made the film. The New York

Times called it "unspeakable ... rotten ...

stupid." Yet John Wayne was undaunted. "That little

clique back there in the East has taken great personal

satisfaction reviewing my politics instead of my pictures,"

he often said. "But one day those doctrinaire liberals will

wake up to find the pendulum has swung the other way.

Foul-Weather Friend

I never once saw Duke display hatred toward

those who scorned him. Oh, he could use some pretty salty

language, but he would not tolerate pettiness and hate. He was

human all right: he drank enough whiskey to float a PT boat,

though he never drank on the job. His work habits were legendary

in Hollywood - he was virtually always the first to arrive on

the set and the last to leave.

His torturous schedule plus the great personal

pleasure he derived from hunting and deep-sea fishing or

drinking and card-playing with his friends may have cost him a

couple of marriages; but you had only to see his seven children

and 21 grandchildren to realize that Duke found time to be a

good father. He often said, "I have tried to live my life

so that my family would love me and my friends respect me. The

others can do whatever the hell they please."

To him, a handshake was a binding contract. When

he was in the hospital for the last time and sold his yacht, The

Wild Goose, for an amount far below its market value, he learned

the engines needed minor repairs. He ordered those engines

overhauled at a cost to him of $40,000 because he had told the

new owner the boat was in good shape.

Duke's generosity and loyalty stood out in a

city rarely known for either. When a friend needed work, that

person went on his payroll. When a friend needed help, Duke's

wallet was open. He also was loyal to his fans. One writer tells

of the night he and Duke were in Dallas for the premiere of Chisum.

Returning late to his hotel, Duke found a message from a woman

who said her little girl lay critically ill in a local hospital.

The woman wrote, "It would mean so much to her if you could

pay her just a brief visit." At 3 o'clock in the morning he

took off for the hospital where he visited the astonished child

and every other patient on the hospital floor who happened to be

awake.

I saw his loyalty in action many times. I

remember that when Duke and Jimmy

Stewart were on their way to my second inauguration as

governor of California they encountered a crowd of demonstrators

under the banner of the Vietcong flag. Jimmy had just lost a son

in Vietnam. Duke excused himself for a moment and walked into

the crowd. In a moment there was no Vietcong flag.

Final Curtain

Like any good John Wayne film, Duke's career had

a gratifying ending. In the 1970s a new era of critics began to

recognize the unique quality of his acting. The turning point

had been the film True

Grit. When the Academy gave him an Oscar for best actor

of 1969, many said it was based on the accomplishments of his

entire career. Others said it was Hollywood's way of admitting

that it had been wrong to deny him Academy Awards for a host of

previous films. There is truth, I think, to both these views.

Yet who can forget the climax of the film? The grizzled old

marshal confronts the four outlaws and calls out: "I mean

to kill you or see you hanged at Judge Parker's convenience.

Which will it be?" "Bold talk for a one-eyed fat

man," their leader sneers. Then Duke cries, "Fill your

hand, you son of a bitch!" and, reins in his teeth, charges

at them firing with both guns. Four villains did not live to

menace another day.

"Foolishness?" wrote Chicago

Sun-Times columnist Mike Royko, describing the thrill

this scene gave him. "Maybe. But I hope we never become so

programmed that nobody has the damn-the-risk spirit."

Fifteen years ago when Duke lost a lung in his

first bout with cancer, studio press agents tried to conceal the

nature of his illness. When Duke discovered this, he went before

the public and showed us that a man can fight this dread

disease. He went on to raise millions of dollars for private

cancer research. Typically, he snorted: "We've got too much

at stake to give government a monopoly in the fight against

cancer."

Earlier this year, when doctors told Duke there

was no hope, he urged them to use his body for experimental

medical research, to further the search for a cure. He refused

painkillers so he could be alert as he spent his last days with

his children. When John Wayne died on June 11, a Tokyo newspaper

ran the headline, "Mr. America Passes On."

"There's right and there's wrong,"

Duke said in The

Alamo. "You gotta do one or the other. You do the

one and you're living. You do the other and you may be walking

around but in reality you're dead."

Duke Wayne symbolized just this, the force of

the American will to do what is right in the world. He could

have left no greater legacy.

Ronald Reagan

Visit

the Ronald Reagan Foundation online

Got something to say about this article? Want to agree (or

disagree) with it? Click the following link to go to the GUNBlast Feedback Page.

|

|

Click pictures for a larger version.

Ruger John Wayne 100th Birthday Commemorative New Vaquero .45

Colt Sixgun.

The John Wayne vaquero is finished in high-polish blue,

and tastefully engraved.

Duke's signature is gold-inlaid on the top of the

barrel.

Bottom of the grip frame attests that the John Wayne

Vaquero is officially licensed by Wayne Enterprises.

Grips are beautifully checkered, and feature

"JW" monograms and a "W" mark underneath.

The trigger is smooth.

Special printed materials include an outer box sleeve

(top) and booklet about the gun (bottom).

Ruger's commemorative red plastic box is specially

decorated for the John Wayne Vaquero.

The John Wayne Vaquero is right at home in this

"Duke" style rig from Sixgunner Leather.

Key lock resides under the grip panel.

Chamber throats measure a perfect .4515 inch.

Grip frame fits perfectly in a Ransom insert made for

the Colt SAA.

As befits this sixgun's status, only the finest cast

bullets will do: Mt. Baldy's 270 SAA.

As a shooter, the John Wayne Vaquero does not

disappoint, as these sub-2" 25-yard 10-shot groups show.

Five-shot 25-yard groups measured 1.5"

Offhand at 25 yards, the John Wayne Vaquero shoots to

point of aim.

|

![]()